Why was fearless and brave SAS hero Paddy Mayne never awarded a Victoria Cross?

Published in the Telegraph Magazine on 14 November 2020.

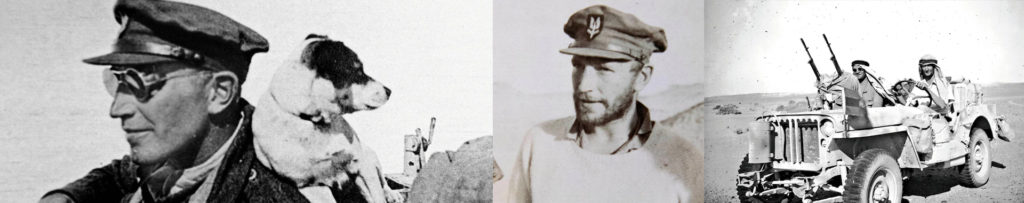

Lieutenant Colonel Blair ‘Paddy’ Mayne

Fearless, wild and brilliant – Paddy Mayne, founding father of the SAS, is reputed to have destroyed more German planes during the Second World War than the RAF’s top ace. So why was his bravery never fully recognised in his lifetime? Ahead of a new BBC drama, military historian Lord Ashcroft examines the extraordinary life – and premature death – of the most controversial Special Forces hero in history.

On a granite plinth in Conway Square in the centre of Newtownards, Co Down, there is a near life-size bronze statue in memory of the town’s most famous son. The inscription beneath it reads: ‘Lt Col Blair ‘Paddy’ Mayne 1915-1955.’

With a modesty that was typical of the man himself, there is no mention that he was a founding father of the SAS, no mention of his astonishing four Distinguished Service Order (DSO) awards from the Second World War, and no mention that Paddy Mayne was arguably the UK’s greatest-ever front-line soldier.

Despite his success on the battlefield, in death, as in life, Mayne divides public opinion. There are those in the Army who consider him, at times (particularly after strong drink), to have been so wild and ill-disciplined that he should never be regarded as a true military great. However, there are plenty more who regard him as a hero who had few betters either as a brave soldier or as an inspirational leader of men.

His later years were marred by heavy drinking. Though he enjoyed playing golf and socialising, he never settled down and had a family, nor even a steady girlfriend. In fact, when he died at the age of 40, in a freak car accident, he was single and lived with his elderly mother, Margaret, and three siblings.

His legacy might long have been forgotten. And yet even today, 65 years after his death – and some 75 years after the Second World War ended – Mayne’s supporters are still campaigning for him to receive a belated Victoria Cross, the UK and Commonwealth’s most prestigious gallantry award. Meanwhile, a new BBC drama, SAS: Rogue Heroes, which has been tipped to star Tom Hardy, is in the pipeline, based on the life of Mayne and other SAS soldiers. Shooting is due to begin next year, with Peaky Blinders’ screenwriter Steven Knight on board.

As someone with a lifetime interest in bravery, including writing six books on courage and amassing the world’s largest collection of VCs, my admiration for Mayne’s gallantry has no bounds. I particularly admire his ‘cold courage’ – he knew the dangers yet repeatedly confronted them. So in the week of Remembrance Day, it is appropriate to recall the extraordinary life and career of a man who became synonymous with the SAS following its formation in 1941.

Robert Blair Mayne was born in Newtownards, to a prosperous middle-class Protestant family on 11 January 1915. The son of a businessman, Blair (as he was known) was the second youngest of seven children – four boys and three girls.

When he was born, the Great War was five months old and Ireland had not yet been partitioned – but the country of his birth was anything but united and the Easter Rising was only 15 months off.

Like the rest of the family, the young Mayne was encouraged to enjoy the outdoors and to play sport. It soon became clear, especially when he started attending the Regent House Grammar School,

that he was an exceptional athlete, his strength matched by his hand-to-eye coordination. He excelled at rugby, cricket, horse riding, fly-fishing, hunting and shooting: the last two sports would come in useful when he was a soldier.

In 1934, aged 19, Mayne began to study law at Queen’s University, Belfast. Here, he shone at boxing, winning the heavyweight title for Irish universities and becoming a finalist in the British universities’ championship. His rugby talents as a second-row forward were recognised three years later when he won the first of six caps for Ireland. He also toured South Africa with the British Lions, taking part in 20 of the 24 Test and provincial matches.

Even then, he was known to like a drink and caused a stir when he went out hunting, shot a springbok and brought it back to the team hotel, then carried it upstairs and dumped it on a window ledge. This was apparently prompted by one of his teammates complaining about the lack of ‘fresh meat’ on the tour.

On his return from South Africa, Mayne graduated from university and qualified as a solicitor. His final game for Ireland came on 11 March 1939, five days after he had joined the Territorial Army when war loomed.

As Nazi Germany prepared to expand its influence, Mayne was 24 years old, just over 6ft 2in tall, fair-haired, broad-shouldered, courteous and shy, including with women.

In late 1939, Mayne and two friends joined a Royal Artillery territorial unit, but the following April he transferred to the Royal Ulster Rifles. Soon the so-called ‘Phoney War’ ended after Germany invaded first Denmark, then Norway, and, later, the Low Countries and France, forcing the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to retreat and evacuate from Dunkirk in May 1940.

Winston Churchill was convinced that, within limits, attack was the best form of defence and called for the formation of a ‘butcher and bolt’ raiding force to strike at enemy targets. Mayne volunteered and was seconded to the newly formed No 11 (Scottish) Commando. His close friend in the Rifles, Eoin McGonigal, a Catholic from south of the border, joined him.

Both men ticked all the key requirements: they were fit, strong swimmers and during training for their new role in Scotland, they were quiet and dedicated.

Mayne’s unit arrived in Cyprus in April. Here, Mayne started drinking heavily and was arrested for emptying his revolver at the feet of a nightclub manager he considered had overcharged for drinks. He was detained for 48 hours.

In the early hours of 9 June 1941, Mayne saw action for the first time in the Syria-Lebanon Campaign, playing a prominent role in the Litani River operation against Vichy French forces. His troop captured some 80 prisoners and several guns, and he was later mentioned in despatches (MiD) for his courage, but he went down with malaria in July.

Mayne was next recruited by Lieutenant Colonel David Stirling, the founder of the SAS, who wanted to use smaller forces for hit-and-run raids behind enemy lines. By September, Mayne was commanding No 2 Troop, L Detachment of the SAS, and was delighted that McGonigal was again serving with him.

However, in November 1941, Mayne took part in a largely unsuccessful raid in Libya that cost McGonigal his life. Mayne was devastated by his death and went to look, unsuccessfully but at great risk, for his friend’s grave. Later he wrote a tender letter to McGonigal’s mother, expressing his condolences for her loss.

For the next year, Mayne participated in many night raids deep behind enemy lines in the deserts of Egypt and Libya, pioneering the use of military jeeps to conduct surprise raids. It is estimated that he personally destroyed up to 100 aircraft on the ground.

For his part in the Wadi Tamet raid on 14 December 1941, which destroyed enemy aircraft and petrol dumps, Mayne was awarded the DSO. He also received a second MiD in February 1942, along with a promotion to captain.

More successes followed as the SAS was reorganised – into the Special Raiding Squadron (SRS) and the Special Boat Section (later the Special Boat Service, or SBS). Mayne was to have command of the former, containing nearly 300 men. Under his leadership, which involved strict discipline and relentless training, the SRS became a formidable fighting unit.

From mid 1943, the focus of Mayne’s war switched to Europe, initially Sicily, where the SRS was chosen to take part in the invasion of the island. On two ships, they arrived off the Sicilian coast on the evening of 9 July, tasked – as part of ‘Operation Husky’ – with capturing and destroying the coastal battery at Capo Murro di Porco.

The citation for Mayne’s second DSO read: ‘By nightfall SRS had captured three additional batteries, 450 prisoners, as well as killing 200 to 300 Italians.’ Perhaps most incredible of all, the SRS had suffered just one man killed and two wounded.

Flushed with success, the SRS were asked to capture the Italian town of Augusta, which they did with a surprise daylight raid. This second raid was also part of the citation for his DSO, which praised Mayne’s ‘courage, determination and superb leadership which proved the key to success’.

Mayne was not wounded during the actions in Sicily and mainland Italy, but he was increasingly troubled by a back injury that was to plague him for the rest of his life. In between battles, he continued to drink heavily and sometimes brawled with his own men.

After flying home to the UK, Mayne was appointed Lt Col 1 SAS Regiment from 7 January 1944, when he was also authorised to create five squadrons. By this point, the focus of attention was turning to the invasion of France. It was soon agreed that the SAS should play to its strengths and operate in small groups behind enemy lines, working with the Maquis, the French Resistance.

The citation for Mayne’s second Bar to his DSO summed up the key role that he played after being dropped behind enemy lines on 8 August 1944.

In April 1945, SAS soldiers were on German soil for the first time, with ‘B’ and ‘C’ Squadrons, under Mayne, keen to get behind enemy lines and wreak more havoc.

On 9 April, while advancing in north-west Germany, ‘B’ Squadron came under heavy fire from farm buildings and a major was killed. When Mayne arrived on the scene, he quickly went into the open and, firing from the shoulder, launched a ferocious onslaught on a farm building until all enemy soldiers in it were dead or wounded.

Next, he drove a jeep in full view of the enemy and with all guns blazing, to rescue two wounded comrades. For this act of bravery, Mayne was recommended for the Victoria Cross, and his actions were supported by witness statements.

And yet higher up in the Army command, the ‘VC’ in the recommendation was crossed out and replaced with ‘3 Bar DSO’. It is not known who took this decision or why. Was it malicious because some saw Mayne as a troublemaker? Or was it a rational decision based on not having done quite enough to be awarded the VC?

By early May the war in Europe was won and Mayne flew back to the UK from Brussels on VE Day before getting involved in the ‘tidying up’ operations in Norway.

In October 1945, 1 SAS was disbanded and the following month Mayne left the Army. After the war, further decorations followed, notably the Legion d’Honneur and Croix de Guerre from France.

However, some senior Army officers felt that Mayne had sometimes been too brutal and callous. David Stirling had rebuked him in 1941 for gunning down an estimated 30 unarmed enemy soldiers who were in their canteen during an operation in the Libyan desert. Mayne had, Stirling felt, ‘overstepped the mark’.

After a post-war spell with the British Antarctic Survey on the Falkland Islands, which was cut short by his recurring back injury, Mayne returned to Newtownards working first as a solicitor and, later, as secretary to the Law Society of Northern Ireland.

For the rest of his life he seemed troubled by physical and mental pain. His back injury prevented him from doing heavy work and it is highly likely that he was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. His fondness for alcohol continued, and he was still prone to binge-drinking.

On 14 December 1955, he attended a meeting of the Friendship Lodge and afterwards continued drinking with some fellow Freemasons in Bangor. He then headed home and drove at speed in his red open-top Riley sports car, swerved to miss an unlit coal lorry and crashed into a telegraph pole. He was found dead in his car at 4am, having fractured his skull, less than a mile from home. He was just 40.

Days later, Mayne was laid to rest at Movilla Abbey cemetery. Roy Magowan, then 16, was one of the last people to see the SAS legend alive when Mayne picked up his car from McMorran’s Garage, where he worked as an apprentice, after it had been repaired.

‘He was a gentle, polite man but I had no idea of his wartime heroics. I thought he was a schoolteacher,’ Magowan told me.

Now 81, he looked emotional as he described watching, through a crack in the garage doors, the funeral cortège of hundreds of mourners snake its way through the town before Mayne was

buried in a family grave.

For 75 years, some of Mayne’s supporters have been angered that he was never awarded the VC. An Early Day Motion (EDM), supported by more than 100 MPs was put before the House of Commons in June 2005. The EDM recognised the ‘grave injustice’ meted out to Mayne and noted even George VI had inquired why the VC had ‘so strangely eluded him’.

It called on the government to mark the 150th anniversary of the VC in January 2006 by ‘instructing the appropriate authorities to act without delay to reinstate the Victoria Cross [for Mayne] given for exceptional personal courage and leadership’.

The EDM was ignored yet, even today, there are calls from everyone from former SAS soldiers to family and locals for Mayne to receive the VC. In August this year, they were encouraged when the Australian government announced it is finally recommending that Ordinary Seaman Edward Sheean receive the VC, a full 78 years after he was killed, aged 18, for an astonishing act of bravery at sea.

The ruling has given new hope to an anonymously run Twitter feed called ‘Blair Paddy Mayne’, which has a pinned tweet that reads: ‘The campaign to ensure that Lt Col Mayne gets the Victoria Cross he should have received must go on.’

Last year Mayne’s uniform and his trunk containing a mass of photographs, documents and memorabilia were gifted to the War Years Remembered Museum in Ballyclare, Co Antrim, by the soldier’s niece, Fiona Ferguson. David McCallion, the founder of the museum, told me, ‘I felt humbled and privileged that this museum was chosen as the home for this incredible collection. Blair Mayne is an iconic hero for this isle and it is vital that his legacy lives on.’

Ferguson, who was 10 when Mayne died, told me, ‘To many, he was a war hero but to me he was a loving, generous uncle. My father used to say of his brother’s lack of the VC, “If he couldn’t have it when he was alive, he wouldn’t have wanted it when he was dead.”’

Did his valour deserve the VC? Absolutely, in my opinion. Should the powers that be now go back and reassess whether he is entitled to receive the award 75 years on? Probably not, simply because it is impractical to review such gallantry awards decades on, especially when the witnesses are dead.

Ultimately, I share the view of Peter Forbes, a maths teacher from Newtownards, an expert on Mayne’s life, who conducts private, unpaid tours championing his hero. He told me, ‘Perhaps Blair Mayne is destined to go down in history as the bravest man never to have been awarded the VC.’