The extraordinary life and courage of Violette Szabó GC

Published in Britain at War in November 2015.

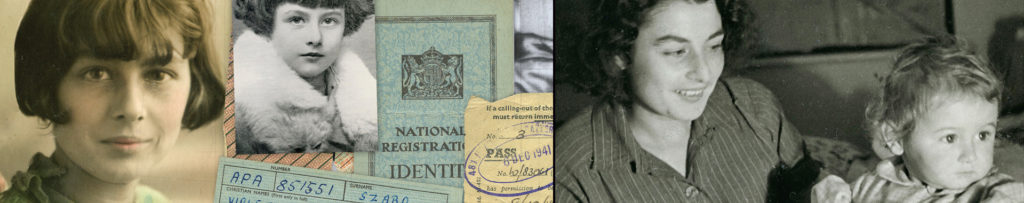

Ensign Violette Reine Elizbeth Szabo GC

“SHE was the bravest of us all,” said Odette Churchill of her fellow George Cross (GC) recipient Violette Szabó. They were words of praise indeed coming from a woman who had herself endured brutal torture at the hands of the Nazis after being captured while working for the French Resistance during the Second World War. Yet Churchill knew – and graciously publicly recognised – that Szabó’s protracted courage was second to none, resulting in her becoming one of only four women in history to receive a direct award of the GC.

In July this year, in my role as a champion of bravery and a gallantry medal collector, I purchased Szabó’s medal group at auction, paying a world-record auction price for a GC for the privilege. By becoming the custodian of these treasured awards for her courage as an undercover Special Operations Executive (SOE) agent, I guaranteed that the medals would remain in Britain and that they would go on permanent public display for the first time. With Szabó’s medal group came a wonderful collection of previously-unpublished documents, letters, photographs and other memorabilia.

Now that this medal group has gone on display at the world-famous Imperial War Museum in London [NB from October 7 2015], I am using this and other material to tell the full story of Szabó’s life and courage. And what a story it is: for Szabó not only received the GC and the French Croix de Guerre but she also, later, inspired a film – Carve Her Name with Pride, starring Virginia McKenna – and she was honoured with a museum in her name. In short, Szabó is undoubtedly one of the greatest heroines of modern history.

Violette Reine Elizabeth Bushell was born in Paris on June 26 1921. Her father was English, her mother French; the couple had met when he was serving in France during the First World War. The young Violette – her married name was to be Szabó – had an older brother and three younger brothers but, being so sporty, she often competed against the four boys on equal terms. As well as being beautiful, with dark hair and olive skin, Bushell had an inner strength that was to remain a vital part of her character for all her life. “She should have been a boy,” her parents agreed, after time and again admiring her toughness.

After criss-crossing England and France, the family finally settled in Stockwell, south London, from 1932. After leaving school in 1935 aged fourteen, Bushell got a job in a French corsetiere and, then, a branch of Woolworths but she switched to working at the Bon Marché store in Brixton, south London, in 1939. When the war broke out later that year, she was still only 18.

From early in the war, Bushell was determined to make her mark and she and a friend, Winnie Wilson, joined the Land Army. On July 14 1940 and to mark Bastille Day, Bushell’s mother urged her to go to the Cenotaph in central London and invite a French soldier home for a meal. Bushell accomplished the task when, accompanied by Winnie, she got talking to a French soldier and asked him back. The man, Sergeant Major Etienne Szabó, a member of the French Foreign Legion, fell in love with Bushell and less than six weeks later – on August 21 1940 – they were married in Aldershot, Hampshire, when he was 30 and she was 19.

Inevitably, their time together was short for Szabó’s husband had to go to fight in North Africa and they did not see each other for a year. They were briefly reunited in Liverpool in the summer of 1941 before Etienne Szabó had to return to duty. They never saw each other again: she was pregnant when he departed, and he was killed at El Alamein in October 1942, four months after the birth of their only child, Tania. Szabó faced an uncertain life as a young widow and single mother, aged 22.

In October 1941, a year before her husband’s death, Szabó, ever keen to “do her bit” for the war effort, had joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), serving with 481 (M) Heavy Anti Aircraft Battery. However, Szabó had to leave the battery for several months for the birth of her daughter, but she then left the baby girl with a friend in Havant, Hampshire, because London was so dangerous during the war.

In late 1942, the SOE, which had been set up in 1940 with the aims of sabotage and subversion behind enemy lines, became aware of the recently-widowed Violette Szabó. In early 1943, she received a letter from a “Mr E. Potter” inviting her for an interview at the SOE’s offices in central London. With her knowledge of French, she was exactly the kind of person the SOE wanted to recruit. Mr Potter – in fact, Selwyn Jepson, the SOE’s senior recruiting officer – explained the job requirements and Szabó expressed a desire to join the organisation. One week later, she met with the SOE for a second time where she was informed of the risks of working behind enemy lines. However, she was desperate to return to France and gain revenge for her husband’s death. Szabó joined the SOE in June 1943, when her daughter was exactly a year old, and she soon underwent training as a secret agent. Brigadier Sir John ‘Jackie’ Smyth, the VC recipient and author, wrote: “Violette was a ‘natural’ for this type of work. She had fluent French, was a born athlete, a very good shot and had the self confidence of a healthy, adventurous, beautiful and life-loving young woman.” In the run-up to her first mission, Szabó met Leo Marks, the SOE code master: all agents were trained to code and decode messages. Marks apparently gave Szabó as her code poem the verse that he had written after learning that his girlfriend had died in a place crash in Canada. It read:

The life that I have is all that I have,

And the life that I have is yours.

The love that I have of the life that I have, Is yours and yours and yours.A sleep I shall have, a rest I shall have,

Yet death will be but a pause,

For the peace of my years, in the long green grass, Will be yours and yours and yours.

By the autumn of 1943, Szabó was well aware of the dangers that lay ahead. I now possess the original hand-written, and witnessed, note that she wrote on November 17 1943: “I hereby appoint Miss Vera Maidment [a friend] & her Mother Mrs Alice Maidment the legal guardian of my child Tania Damaris Desiree Szabó, in the event of my death.” She signed it simply “V. Szabó”.

Her first mission took place in April 1944, two months before D-Day, having been given the identity of “Corinne Reine Leroy”, the last two names belonging to her mother. She was dropped into France on April 5 on a high-risk operation at a dangerous time. Her job was to act as a courier to a French Resistance leader whose group, based in Rouen, had been broken up. Because it was not safe for Philippe Liewer, the man accompanying her, to be seen in Rouen, Szabó was given the role of visiting the city. She had to travel alone from Paris to Rouen and make contact with those Liewer thought had been “unmolested” by the disbandment of the group. At the time, Rouen was in Occupied France and was in the specially restricted area of the Channel ports.

Szabó carried out her first mission calmly and competently: she made her contacts and prepared a comprehensive report on what she found. Furthermore, she brought back a German “Wanted” poster, taken from a street in Rouen, which bore a photograph of Liewer and his wireless operator based on their false identity papers. This was valuable information because it showed that at that time the Gestapo had not been able to establish their true identities. Szabó’s mission was so successful that after less than four weeks in France, she, along with Liewer and his wireless operator, were picked up in a Lysander aircraft and brought back to Britain. Szabó was reunited with her parents, who were by now caring for her daughter. The family’s time together was, however, all too short.

Szabó’s superiors soon had another mission for her – this one even more dangerous than the last. She was left under no illusions that she might well not return. She had made a will earlier in the year – leaving everything she possessed to her daughter – and told her parents that if they did not hear from her they must not inquire into her whereabouts. Her farewell to her daughter at around the time of Tania’s second birthday was deeply emotional because she realised she might never see her again and that, if this happened, Tania would be orphaned.

In the early hours of June 8 1944, shortly after the D-Day landings, Szabó was back on French soil with new orders to assist the Resistance. She was to act as a courier for the same chief and wireless operator whom she had worked for in Rouen. Her code name for the mission was again “Corinne”, while she was given the fake identity of “Madame Villeret”. After parachuting from a Liberator aircraft, she headed for an established Maquis – a guerrilla group – in central France, south of Châteauroux. Its role was to orchestrate attacks on German troops who were moving up to reinforce units opposing the Allied landings in the Normandy area. The Maquis was spread in small groups over a wide area: Szabó’s role was to carry instructions and money to the groups north of the main Maquis.

Szabó was offered a lift by car from a young French Resistance fighter called Jacques Dufour, codenamed “Anastasie”, who knew the terrain well. On June 10 1944, after just three days back in the country, Szabó was being driven by Dufour from Sussac to Salon-la-Tour. On the way, they stopped to pick up a friend of Dufour’s, Jean Bariaud, and Szabó insisted on taking her own Sten gun concealed in the car in case they encountered trouble.

As the group headed into the village of Salon-la-Tour, they saw a German roadblock at a crossroads. They decided to stop the car and make a run for it: Bariaud escaped, while Szabó and Dufour, who had the Sten gun, fired at the Germans, killing or wounding at least one soldier. As they retreated towards a wood, Szabó was wounded.

Aware that she was slowing down Dufour and determined that he should escape, she ordered him to flee while she continued engaging the enemy with the Sten gun, crouched beneath an apple tree. When she eventually ran out of ammunition, she was captured. When confronted by a smirking SS officer, she laughed and then spat in his face with typical defiance. Bariaud raised the alarm when he returned to Sussac, while Dufour also escaped, apparently by hiding in a haystack or a wood-pile.

I now possess the original translation of a letter, dated April 19 1958, in which a fellow prisoner, Madame Marie Lecomte, told Szabó’s parents how their daughter had been involved in a “terrific battle” which had preceded Szabó’s capture. Lecomte, who described herself as like a “second mother” to Szabó, also told how the young woman was “brutally assaulted” and “suffered terribly” at the hands of her interrogators. She said she was sorry to “reopen all your wounds again” but she was fulfilling a promise to “your very Dear daughter” to pass on such information to her [Szabó] parents. The letter was written, following the translation, in the hand of Szabó’s mother, Reine Bushell.

Despite her injuries received in the battle before her capture, Szabó had been taken to the military prison in Limoges where she was brutally interrogated. Eyewitnesses saw her limping across the courtyard to the Gestapo offices for her twice daily interrogations. A plan was made by the Resistance to spring her from prison but on the day of the escape bid she was transferred to Fresnes prison, near Paris. After further torture at the Gestapo headquarters in Avenue Foch, she went back to Fresnes where she spent her twenty-third, and final, birthday racked with pain. Through her ordeal, she repeatedly told herself: “I must not show any fear.” She told her torturers nothing of use to them.

The conditions in which Szabó was kept for the next five months were appalling but there is no firm evidence that she continued to be tortured. After a short stay in Saarbrücken, she went to Ravensbrück on, or about, August 25 1944. Those moved with her included Denise Bloch and Lilian Rolfe, fellow SOE operatives. At one point, the train had come under heavy bombing from the RAF and the German guards, fearing for their own lives, jumped off it. On board were 37 male PoWs crammed into two compartments. Szabó, who was shackled to another woman prisoner, managed to fill a jug of water in the train’s toilet and crawled back to give it to the desperately thirsty and undernourished PoWs. One of them, Wing Commander Forest Yeo Thomas (the so-called ‘White Rabbit’ and himself later awarded the GC) always remembered the incident and Szabó’s kindness, and he later reported it back to London.

After a short stay at Ravensbrück, Szabó was transferred to a working camp at Torgau and participated in a mass protest against working with munitions. As a result, she and her fellow protesters were sent to a punishment camp at Königsberg. In the sub-zero winter temperatures, the women PoWs worked in thin clothes chopping wood and clearing the land. For nourishment, they received only weak soup and tiny amounts of bread. In January 1945, the three women were transferred back to Ravensbrück. By now Szabó was in a desperately weak physical condition and she was convinced she was going to die.

Some time between January 25 and February 5, the three women – Szabó, Bloch and Rolfe – were taken to Ravensbrück’s execution alley, where their death sentences were read to them. Finally, they were shot in the back of the neck as they kneeled, one executed after the other, before their bodies were incinerated. It is understood Szabó was shot last, having first seen the other two women executed. She was some five months short of her 24th birthday when she was killed.

It was only on April 13 1946 that the precise fate of the three women became known, from the second-in-command at Ravensbrück. At the time, he was being questioned in Hamburg by Vera Atkins of the SOE, who was determined to learn what had happened to the courageous trio. Szabó’s GC was announced on December 17 1946 when the citation ended: “She was arrested and had to undergo solitary confinement. She was then continuously and atrociously tortured but never by word or deed gave away any of her acquaintances or told the enemy anything of any value. She was ultimately executed. Madame Szabó gave a magnificent example of courage and steadfastness.”

I now posses the original letter from the War Office to Mr and Mrs Bushell, dated December 18 1946, informing them of their daughter’s posthumous GC. It concludes: “Though no award can in any way assuage your grief, it is gratifying to know that the gallant services of your daughter have been brought to the notice of His Majesty, who has recognised them in according this honour.”

On January 28 1947, Tania Szabó, by now five years old and wearing the dress her mother had purchased in Paris on her first mission to France, received her mother’s GC from George VI in an investiture at Buckingham Palace. “It’s for your mother. Take great care of it,” the King told the young girl. Later Tania clutched the GC and told photographers: “It’s for mummy. I’ll keep if for her until she comes home.” In 1949, Charles and Reine Bushell emigrated to Australia to begin a new life, taking Tania, their granddaughter, with them.

The memorials to Szabó include a plaque at Lambeth Town Hall, in the south London borough where she spent much of her childhood. Szabó’s remarkable story was turned into a film, Carve Her Name with Pride, based on the book by RJ Minney and starring Virginia McKenna. The 1958 film helped perpetuate the moving story of the so-called “Code Poem” written by Leo Marks.

Virginia McKenna was among many who supported an appeal launched in 1998 to open a museum in Szabó’s honour in the grounds of the home of one of the secret agent’s aunts. The museum eventually opened in Herefordshire on June 24 2000 – the closest Saturday to what would have been Szabó’s seventy-ninth birthday.

I purchased Szabó’s medal group at a Dix Noonan Webb auction in London on July 22 this year, paying £260,000 (plus a buyer’s premium of £52,000), for the honour of becoming the custodian of the awards. They were sold by Tania Szabó, who is now 73, to help secure her future and meet the cost of a fire at her home. I was delighted with her public response once she learned that I was the purchaser of the medal group: “I’m very happy with the result. They’re going into a safe place where people will be able to view them – many thousands of people – so a good result.”

It was the first time that a GC medal group had ever fetched a six-figure sum at auction. The GC was instituted by George VI on September 24 1940 and was intended to be awarded to civilians and servicemen, and women, who displayed great bravery that was not in the face of the enemy.

During the past 75 years, Szabó is one of only four women to have been directly awarded the GC, three of whom received it posthumously. I feel privileged to be the custodian of her medal group and I am delighted that is has gone on public display in the Lord Ashcroft Gallery at the Imperial War Museum in London from early October. As her daughter Tania has stated, Szabó lived a life that was “short but lived to the full, with much happiness, joy, some deep sadness and great endeavour”.

It was Charles Bushell, Szabó’s father, who summed up his daughter and her courage in a poem, Faithful Even Unto Death, written long after her death. Towards the end of the poem, he wrote:

“The fatal shots were fired, and to the world was lost,

Madame Violette Szabó, how well she earned her Cross.

Never to be forgotten, this girl aged twenty-four

Torture could not break her, she was British to the core.”