HERO OF THE MONTH – DECEMBER 2013

Published in Britain at War in December 2013.

Major John “Jim” Almonds MM & Bar

Is it possible for a professional soldier to be a ruthless killer and also have great compassion for the enemy?

Many military men over the years have displayed one trait or the other but to achieve both is anything but easy. Some soldiers would see any concern for the enemy as a sign of weakness, while many of those overly-worried about the enemy would have difficulty being necessarily brutal even in the heat of battle.

Yet there is one soldier who undoubtedly displayed both traits over many years. Step forward the appropriately named “Gentleman Jim” Almonds, one of the most remarkable men ever to pull on a British military uniform.

“Jim Almonds always ran to the battle,” wrote the late Earl [George] Jellicoe, then President of the Special Air Service Regimental Association. “He was one of the first twelve men who joined David Stirling when he founded the SAS at Kabrit in early September 1941. Physically tough and with the self-discipline and mental strength never to give up whatever the circumstances, he yet showed that personal humility that led to his nickname [Gentleman Jim].”

Almonds thrived on adversity and relished any war-time challenge. Yet, he was anything but headstrong and reckless. Instead, he was intelligent and disciplined and also determined to survive his endless “scrapes” if only to embark on more adventures. Ultimately however, he would always display an incredible respect for the enemy and an old-fashioned sense of “fair play”.

The son of a smallholder, John Edward Almonds was born in Stixwould, Lincolnshire, on 6 August 1914. He made his first – unsuccessful – attempt to join the Army on his fourteenth birthday in 1928 and he eventually joined the Coldstream Guards on his eighteenth birthday in 1932.

Almonds unofficially changed his name from “John” to “Jim” out of convenience – if anyone called out “John”, half the barrack room looked up. Ever practical, he volunteered to be called “Jim”. The “Gentleman” tag came later because, although 6 ft 4 ins tall and fearsome in battle, he was gentle, calm and thoughtful in the company of his comrades.

Early in the Second World War, he became a member of No. 8 Guards Commando, led by Lieutenant Colonel Bob Laycock. Almonds and three other Special Forces men comprised the famous “Tobruk Four” who used tactics that would later be carried into the SAS.

Operating largely at night around the besieged natural seaport in Libya, the team reconnoitred enemy positions and made sporadic attacks on enemy forces.

In his authorised biography of SAS founder David Stirling, Alan Hoe wrote: “Sergeant ‘Gentleman Jim’ Almonds…was in many ways to the desert born. In this environment he was totally at home. He excelled in the velvet darkness and revelled in the vast emptiness of North Africa.”

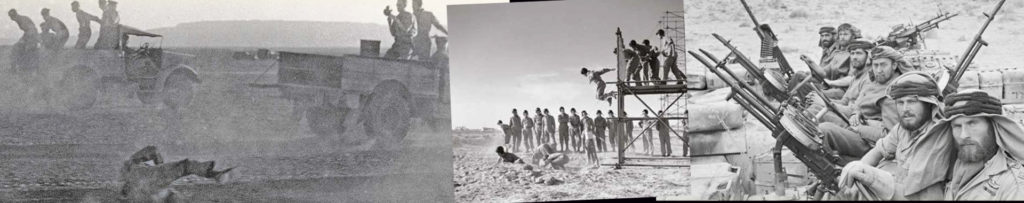

Stirling brought the Tobruk Four into L Detachment of the SAS Brigade, formed in the summer of 1941. Soon he was involved in specialised, and highly dangerous, training for new missions.

His diaries chronicle his hazardous parachute and endurance training, experimental training missions and early raids behind enemy lines. The training itself was awesome, including practising parachute landings by rolling from the back of a truck at up to 30 mph. On 6 October 1941, he wrote: “Afternoon spent jumping backwards from a lorry at twenty-five miles per hour. Three broken arms and a number of other casualties. Broken bones through training now six.” Quite apart from the training dangers and the times when he came under “normal” enemy fire, he narrowly escaped death no less than nine times.

Such times – the early days of parachuting – were not for the faint-hearted. On 17 October, he noted: “Two of the boys killed. Chutes never had a chance to open. Brought back across the canal by boat.” It was not the easiest preparation for the next day, when Almonds had to make his first parachute jump. By now, Gentleman Jim already had a fearsome reputation. It was no surprise that when Paddy Blair Mayne – later to be awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) and three Bars – joined the clandestine unit at Kabrit, he chose Almonds as his troop sergeant.

Almonds and his comrades were prolific in their missions. For example, on 14 December, Almonds and Lewes carried out a successful enemy attack on the main Tripoli coastal road. After arriving at Mersa Brega, they spotted the lights of a large house and fort used as an enemy staging post. There were just the two of them but they pulled in and parked their captured lorry among the Italian and German trucks. They placed bombs on the parked enemy vehicles, while under fire from inside the fort, destroying several enemy transport and coming out of the ‘beat up’ uninjured.

Almonds’ Military Medal was announced in November 1942 when the confidential recommendation from Stirling stated: “This NCO has at all times and under the most testing conditions shown great powers of leadership. After a raid on Nofelia aerodrome [Libya], he took command of his party after his officer had been killed. He showed great resource in managing to extricate this party with only one casualty, although all but one of his trucks had been destroyed. On another raid in the Agheila area, he led a party which destroyed five heavy enemy MT [military transport] and he participated in shooting up an enemy post in this locality.”

Almonds was captured by the Italians during a later SAS mission, but was awarded a Bar to his MM (the equivalent to a second MM) for his two escape attempts. The decoration was announced in April 1944 after the confidential recommendation had stated: “Captured at Benghazi on 14 September 1942, this NCO was first taken to Campo 51 (Altamura). While here Almonds and three others, on 4 February 1943, bribed an Italian officer and sentry with coffee and remained working in the Red Cross hut till it was dark. The officer was decoyed by one PoW and the others then overpowered the sentry and gagged him. Almonds had a map stolen from a RC priest’s Bible, and had constructed a compass. The four PoWs travelled over the hills by night through bad and rainy weather and reached the coast after twelve days. They could find no boat of any kind, were too weak to travel further and were therefore forced to give themselves up. At the time of the Armistice, Almonds was in Campo 70 (Monturano) and was sent out by the SBO [Senior British Officer] to watch the coast road. While out he was told by an Italian that the Germans had taken over the camp. He therefore made good his escape and set out westwards. He contacted American forces on 14 October 1942.”

Yet there are at least two anecdotes which bear testimony to Almonds’ sense of compassion. During one mission behind enemy lines in French-occupied France – an episode that Almonds dubbed – “the French picnic” – the SAS wreaked havoc blowing up railway lines, bridges and ammunition lines in the summer of 1944.

Never one to employ or permit unnecessary violence, he rescued a captured German motorcycle dispatch rider from the French Maquis (resistance). During the two-month operation, “Fritz”, as the German was dubbed, was made to do the housework and cooking. Yet, later, as the US forces advanced, Almonds decided to let Fritz live, choosing his moment to allow him to slip away back to the German lines so that he would not be shot by the American forces or accused of fraternisation with the enemy by his own side.

It was Lorna Almonds Windmill, herself an ex-Army captain, who published a splendid book about her father twelve years ago. Gentleman Jim: The Wartime Story of a Founder of the SAS ends with an anecdote from the last year of the war that I would not attempt to improve upon:

“After returning to the UK, he [Almonds] was out driving one day with Leslie Bateman [his comrade and friend] when they saw two Italian PoWs toiling in the fields, helping to bring in the harvest. ‘Stop the car, Les,’ he said. He patted his pocket and looked at his friend. ‘Have you got any cigarettes?’

“Bateman said he had, and Almonds had some on him too. He put them all together, got out of his car and picked his way across the field to the two PoWs. They stopped work, amazed and slightly apprehensive at the sight of a British army officer coming towards them. ‘This,’ he said to them, ‘is for you, because the Italian people were very kind to me and looked after me when I was an escaping prisoner of war in Italy.’

“The two men, at first stupefied, were quickly all smiles and responded with salutes and much bowing and scraping. ‘Grazie, grazie, Il Capitano,’ they said. It was a small gesture, but something about it brought tears to Bateman’s eyes. It was not only for good manners and his lack of swearing that my father was known as ‘Gentleman Jim’.”

Almonds, who rose to the rank of major, continued to serve with distinction in the SAS for the remainder of the war – and after it.

He died in his home county of Lincolnshire on 20 August 2005, aged ninety-one. Almonds, who had been married for 57 years, was survived by his son and twin daughters.

When I purchased Almonds’ gallantry and service medals at auction in December 2007, they came with his remarkable wartime diaries of over 20,000 words and other memorabilia from his incredible military career.

In the spring of 2011, Almonds’ gallantry and service medals went on public display for the first time along with a small selection of my other previously unseen Special Forces medals. The occasion was the British Antique Dealers’ Association (BADA) Antiques and Fine Art Fair in central London and I was delighted that so many people took time to come and see part of my Special Forces collection.

With “Gentleman Jim” Almonds’ passing eight years ago, we lost a man as proud to fight shoulder to shoulder with his comrades as he was willing to show kindness to the enemy if he felt it appropriate. With his death, Britain undoubtedly lost one of the most complete soldiers that ever lived.