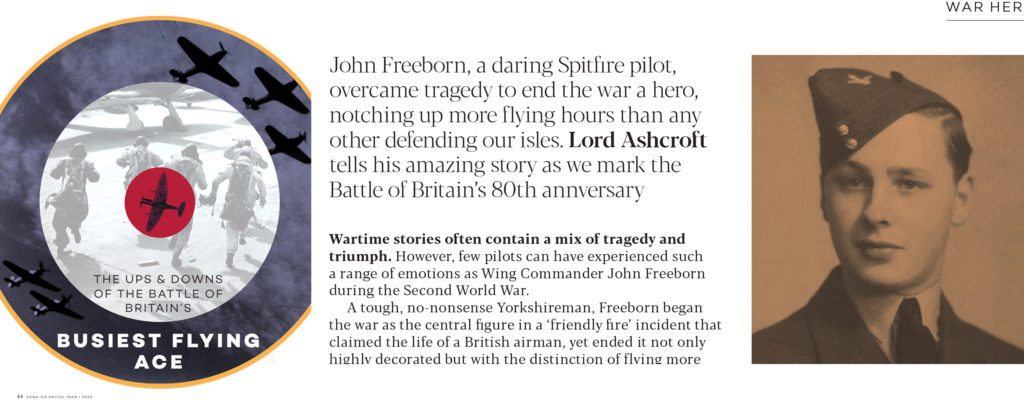

John Freeborn, a daring Spitfire pilot, overcame tragedy to end the war a hero, notching up more flying hours than any other defending our isles. Lord Ashcroft tells his amazing story as we mark the Battle of Britain’s 80th anniversary.

Wartime stories often contain a mix of tragedy and triumph. However, few pilots can have experienced such a range of emotions as Wing Commander John Freeborn during the Second World War.

A tough, no-nonsense Yorkshireman, Freeborn began the war as the central figure in a ‘friendly fire’ incident that claimed the life of a British airman, yet ended it not only highly decorated but with the distinction of flying more Battle of Britain hours than any other RAF pilot.

My interest in bravery spans more than half a century: largely as a result of listening, as a boy, to my late father Eric describe his experiences during the D-Day landings of 6 June, 1944, when his Commanding Officer was shot dead at his side and my father was wounded.

My passion for courage has seen me write six books on bravery and build the world’s largest collection of Victoria Crosses. Yet I am still inspired by stories of great gallantry and, to mark the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Britain, this is my personal tribute to Wing Commander Freeborn DFC (Distinguished Flying Cross) and Bar.

Born on 1 December 1919, John Connell Freeborn was the son of a Leeds banker. Although bright, his dislike of petty authority meant that he was relieved to leave his grammar school. At 18, he joined the Reserve of Air Force Officers. He commenced pilot training and went solo after just four hours and 28 minutes logged flying time, a little over half the typical amount for trainee pilots. He was duly granted a short service commission in the RAF in January 1939.

Freeborn initially flew Gloster Gauntlets but from February 1939, having joined 74 (Tiger) Squadron, he flew Spitfires. With the Second World War only days old, on 6 September 1939 he was involved in an action later dubbed the ‘Battle of Barking Creek’.

In a tragic misunderstanding, two Hurricanes from 56 Squadron were intercepted and shot down by 74 Squadron, thereby becoming the first victims of Spitfire ‘friendly fire’.

One pilot survived his crash-landing but the other, whom Freeborn had shot down, was killed: Pilot Officer Montague Hulton-Harrop was the first RAF pilot to die in the Second World War. Freeborn and a fellow pilot were court martialled but they were acquitted of any liability or blame. However, the incident led to a complete overhaul of Fighter Command’s plotting system for tracking Allied and enemy aircraft.

Freeborn, who was only 19, was left distraught by the accident but became all the more determined to cover himself in glory in the skies. He was heavily engaged in the air battles to save lives on the ground during the retreat of the British Expeditionary Force to Dunkirk in May 1940.

During one combat, his Spitfire was badly damaged and he crash-landed on a beach near Calais. Undaunted, he hitched a lift from a returning British aircraft and was soon back flying. During late May, he claimed a Messerschmitt 109 destroyed and three enemy aircraft as ‘probables’.

However, it was during the Battle of Britain that Freeborn repeatedly excelled, flying into action time and time again against enemy fighters and bombers. On 10 July 1940, the opening day of the Battle of Britain, he shot down an Me 109 over Kent. Success after success followed in aerial dogfights and, on 11 August, he claimed three ‘kills’ and a ‘probable’, flying four missions in just eight hours.

At the height of the Battle of Britain, on 13 August 1940 and in the rank of Flying Officer, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. His citation stated: ‘This officer has taken part in nearly all offensive patrols carried out by his squadron since the commencement of the war, including operations over the Low Countries and Dunkirk, and, more recently, over the Channel and S.E. of England. During this period of intensive air warfare he has destroyed four enemy aircraft. His high courage and exceptional abilities as a leader have materially contributed to the notable successes and high standard of efficiency maintained by his squadron.’

Freeborn was undoubtedly one of those whom Winston Churchill was referring to in his famous speech when he said: ‘Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.’

The Battle of Britain, which ended on the last day of October, had resulted in the loss of 544 British, Commonwealth and Allied aircrew. A further 522 were wounded. But the Luftwaffe had fared far worse and the likelihood of invasion had been avoided.

Freeborn’s successes in the skies continued and, on 5 December 1940, he shot down two Me 109s, shared another and damaged a fourth. He was awarded a Bar to his DFC (effectively a second DFC) on 25 February, 1941, when his citation stated: ‘This officer has continuously engaged in operations since the beginning of the war. He has destroyed at least 12 enemy aircraft and damaged many more. He is a keen and courageous leader.’

For the rest of the war he held several key training and operational roles. He was back in the UK at the end of the war but departed the RAF in 1946, claiming it was run by ‘nincompoops’. He qualified as a driving instructor and then later worked as a company director.

Shortly before his death, Freeborn said that the British pilot he had accidentally killed more than half a century earlier, remained in his thoughts. ‘I think about him nearly every day. I always have done. I’ve had a good life – and he should have had a good life too.’

Twice married, with a grown-up daughter from his first marriage, Freeborn died on 28 August 2010, aged 90. I feel privileged that, as part of my medal collection, I am the custodian of his medal group, for we must never forget the bravery of ‘the few’.