Proof human kindness can overcome the hatred of war

Published in the Mail on Sunday on 11 August 2019.

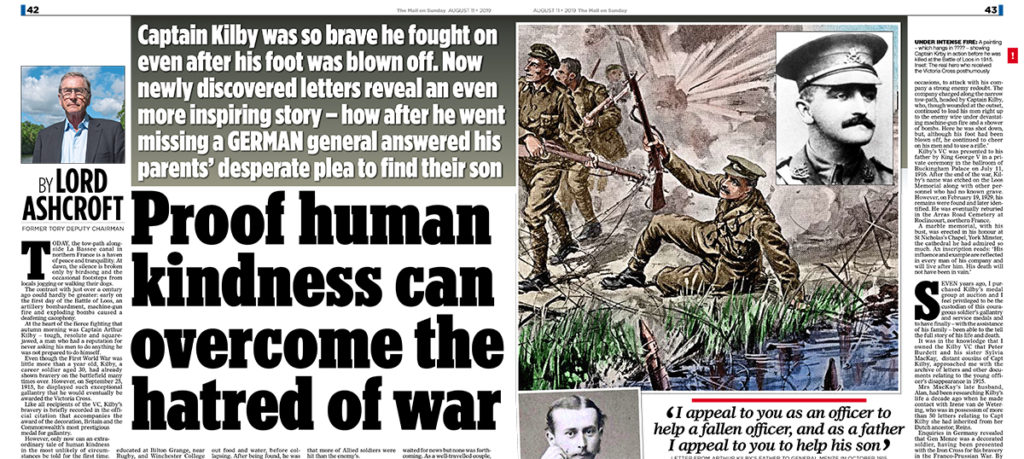

Captain Arthur Kilby

The bravery of a hero British First World War soldier and how a GERMAN general answered his parents’ plea to find their missing son.

- British Captain Kilby was so brave he fought on even after his foot was blown off

- Kilby went missing and his parents undertook a desperate search to locate him

- They were assisted in their task by none other than a German army officer

- Letters show how the German general answered Kilby’s parents pleas to find him

Today, the tow-path alongside La Bassee canal in northern France is a haven of peace and tranquillity.

At dawn, the silence is broken only by birdsong and the occasional footsteps from locals jogging or walking their dogs.

The contrast with just over a century ago could hardly be greater: early on the first day of the Battle of Loos, an artillery bombardment, machine-gun fire and exploding bombs caused a deafening cacophony.

At the heart of the fierce fighting that autumn morning was Captain Arthur Kilby – tough, resolute and square-jawed, a man who had a reputation for never asking his men to do anything he was not prepared to do himself.

Even though the First World War was little more than a year old, Kilby, a career soldier aged 30, had already shown bravery on the battlefield many times over.

However, on September 25, 1915, he displayed such exceptional gallantry that he would eventually be awarded the Victoria Cross.

Like all recipients of the VC, Kilby’s bravery is briefly recorded in the official citation that accompanies the award of the decoration, Britain and the Commonwealth’s most prestigious medal for gallantry.

However, only now can an extraordinary tale of human kindness in the most unlikely of circumstances be told for the first time.

For relatives of the officer have provided me with an archive of letters and documents, more than a century old, that tell of the determined efforts of Kilby’s parents to locate their missing son, who they believed had been wounded in battle and taken prisoner.

The tender letters also reveal how they were assisted in their task by none other than a German army officer they had met in Italy eight years before the outbreak of the so-called ‘war to end all wars’.

Despite Britain and Germany being involved in a bitter conflict that would claim 16 million lives, General Amandus Menze was so touched by Kilby’s parents’ plight that he went to enormous lengths to help locate their son.

This is the full, remarkable story of Captain Kilby’s life – and death.

Arthur Forbes Gordon Kilby was born in Cheltenham on February 3, 1885. He was the only son of Sandford Kilby, who had worked for the Bengal Police in India, and his wife Alice.

The young Kilby was educated at Bilton Grange, near Rugby, and Winchester College before preparing for a military career by spending time in Frankfurt. He then attended the Royal Military College, Sandhurst.

In August 1905, aged 20, he was commissioned into the 1st Battalion, The South Staffordshire Regiment, as a second lieutenant.

A little more than two years later, Kilby was promoted to the rank of lieutenant, and on April 1, 1910, he was made captain. Kilby was a talented linguist, speaking French, Spanish, German and Hungarian.

After the outbreak of the Great War in early August 1914, Kilby, by then serving with his regiment’s 2nd Battalion, was one of the first to embark for the Western Front.

He arrived in France on August 13 as part of the British Expeditionary Force and, within 12 days, saw his first action at Maroilles.

The following day, August 26, his brigade was ordered to withdraw and Kilby was sent to the rear-guard to supervise their retreat.

After intense fire from German artillery, he was badly concussed by a shell. In the chaos, Kilby became separated from his unit and wandered alone for hours without food and water, before collapsing.

After being found, he was treated for shell-shock, spending nearly a month in hospital, before rejoining his battalion on September 24.

In October, his battalion moved north to the Ypres sector before heading north-west of Becelaere, where Kilby executed ‘a brilliant counter-attack’ and was awarded the Military Cross (MC), as well as subsequently being Mentioned in Despatches.

Wounded in the right arm and lung by a rifle bullet, he was forced to return to England for treatment.

Although he never fully recovered the strength in his right hand, Kilby rejoined his battalion in May 1915 and once again became involved in the thick of the fighting. In August, he was recommended for the Distinguished Service Order (DSO).

However, before a decision on this could be taken, the chaotic events of September 25, 1915 – the opening day of the Battle of Loos – intervened.

The South Staffordshire attack began about 6.30am, despite the fact that some members had been badly affected by an Allied gas attack, their first of the war. An unfavourable wind meant that more of Allied soldiers were hit than the enemy’s.

Kilby went forward along the narrow tow-path, where he and his men came under intense fire from both sides of the canal. Early on, Kilby was wounded in the hand, but still he and his men pressed on towards the enemy wire.

As they were exposed to an onslaught of stick grenades thrown from the enemy redoubt, one of Kilby’s feet was shattered by an explosion. Yet still he defied terrible pain to urge his men on, firing at the enemy with his rifle.

The situation, however, eventually became utterly hopeless and at 8am the order was given to withdraw.

Only 20 men from the battalion succeeded in making it back to the British trenches. Nearly 300 from the unit were killed or wounded, including 11 officers.

Kilby was one of the many whose whereabouts were not known, even though his men had staged a prolonged search for the officer they so admired.

Back at their home in Leamington Spa, Kilby’s parents, having been told their son was missing in action, waited for news but none was forthcoming.

As a well-travelled couple, they decided to recruit the help of friends on the Continent but, in particular, the veteran Prussian officer General Menze, whom they had met on holiday in Italy in 1906 and who now lived in Berlin.

They were able to communicate with the German officer through another friend, Dutch woman Reins van de Wetering.

Because Holland was neutral in the conflict, her letters passed freely to both the UK and Germany. The Kilbys also needed her to translate their letters because, unlike their son, they did not speak German.

On October 1, Mr Kilby wrote to Gen Menze reminding him that they had played chess together in Villa Castagnola in Lugano in 1906, and then asking him for help.

‘Our countries are at war but I do not feel that necessarily changes our feeling of humanity and sympathy between German and English gentlemen,’ he wrote.

He provided details of his son’s disappearance, adding: ‘He is my only son. I appeal to you as an officer to help a fallen officer in trouble, and as a father I appeal to you to help his son. If the position were reversed, and I were asked to help you, I should so unhesitatingly.’

In the hope that his son was alive, Mr Kilby added: ‘If you would arrange to help him with clothes, money or comforts or can and will do anything to mitigate his suffering, you will have the lasting gratitude of his mother, sister and father, who will of course repay any money spent on his account.’

Throughout October and the first half of November, the general carried out extensive enquiries into Kilby’s whereabouts, twice writing to the family.

In a handwritten letter dated November 19, 1915, he told them he would let them know if he received information, adding: ‘I will do anything in my power to relieve your worries about your son’s welfare.’

However, the general warned: ‘What worries me is that your son has not yet written to you himself.

‘All prisoners are allowed to write to relatives. I don’t want to conceal from you that it is not a good sign…’

On November 25, 1915, Mrs Kilby wrote to the general to thank him for his kind letters, adding: ‘I can assure you the subject of your search is worthy of it. He is deeply respected and beloved by all ranks in his regiment and his loss is deeply deplored, and in his private life he has a blameless character, his faults being few and trifling.’

She also included postcards detailing her son’s disappearance for him to circulate with information in German as well as English.

In another letter to the general dated December 16, 1915, Mrs Kilby had encouraging news from the Army: ‘Capt Kilby was wounded in the leg and [the] informant [a private in the regiment] saw him taken prisoner by the Germans.’

She added: ‘Pray that it may prove so, and that this may help you in the kind search you are making, and for which we cannot thank you sufficiently.’

However, on February 2, 1916, the family’s growing hopes for their son’s survival were cruelly dashed in a letter from Gen Menze addressed to Mr Kilby: ‘Finally, I got a message about your son today and I will share it with you immediately, even though it will be difficult for me.’

The general had been told by the commander of the regiment confronting the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment, that Capt Kilby had been killed during the battle and later buried.

Adding his commiserations, the general said: ‘It might give you comfort that your son died a hero in front of his comrades.’

On February 21, 1916, Mr Kilby wrote a long letter to the general thanking him ‘from the bottom of my heart for all your kindness’.

He stated: ‘No one could possibly have done more than you have done and I am sure it was your most ardent desire to relieve our anxiety and to befriend my boy. I often wonder at my presumption in seeking your help on the strength of such a slight acquaintance. My greatest friend could not have responded with greater kindness or alacrity.’

It also emerged that the enemy had constructed a simple wooden cross where Kilby was killed that read: ‘The Kilby family may think of their son with pride, as we remember him with respect.’

It was some consolation that Kilby was awarded a posthumous VC, an award announced on March 30, 1916.

The citation, which revealed that one of his feet had actually been blown off in the battle, stated: ‘For most conspicuous bravery. Captain Kilby was specially selected, at his own request, and on account of the gallantry which he had previously displayed on many occasions, to attack with his company a strong enemy redoubt.

The company charged along the narrow tow-path, headed by Captain Kilby, who, though wounded at the outset, continued to lead his men right up to the enemy wire under devastating machine-gun fire and a shower of bombs. Here he was shot down, but, although his foot had been blown off, he continued to cheer on his men and to use a rifle.’

Kilby’s VC was presented to his father by King George V in a private ceremony in the ballroom of Buckingham Palace on July 11, 1916.

After the end of the war, Kilby’s name was etched on the Loos Memorial along with other personnel who had no known grave.

However, on February 19, 1929, his remains were found and later identified. He was eventually reburied in the Arras Road Cemetery at Roclincourt, northern France.

A marble memorial, with his bust, was erected in his honour at St Nicholas’s Chapel, York Minster, the cathedral he had admired so much.

An inscription reads: ‘His influence and example are reflected in every man of his company and will live after him. His death will not have been in vain.’

Seven years ago, I purchased Kilby’s medal group at auction and I feel privileged to be the custodian of this courageous soldier’s gallantry and service medals and to have finally – with the assistance of his family – been able to the tell the full story of his life and death.

It was in the knowledge that I owned the Kilby VC that Peter Burdett and his sister Sylvia MacKay, distant cousins of Capt Kilby, approached me with the archive of letters and other documents relating to the young officer’s disappearance in 1915.

Mrs MacKay’s late husband, Alan, had been researching Kilby’s life a decade ago when he made contact with Irene van de Wetering, who was in possession of more than 50 letters relating to Capt Kilby she had inherited from her Dutch ancestor, Reins.

Enquiries in Germany revealed that Gen Menze was a decorated soldier, having been presented with the Iron Cross for his bravery in the Franco-Prussian War. By the time of the Great War, he was retired.

He died, in his home city of Berlin, in 1918, aged 71. By coincidence, he died on the very day – April 21 – that Manfred von Richthofen, the so-called Red Baron, was shot down and killed over northern France.

I travelled to northern France as part of my research for this article. I placed a regimental wreath besides Kilby’s gravestone at the Arras Road Cemetery and paid my respects to a war hero whose courage must never be forgotten.

The efforts of his parents and the German general to trace his whereabouts are heart-rending and uplifting at the same time.

Even in war, human kindness can rise above the mayhem as it did in the events surrounding the life and death of Captain Arthur Kilby, VC, MC.